By Lorraine Pratley.

This article presents a chronological account of the 1989 Tiananmen movement—referred to by the Chinese government as the “1989 political disturbance.” It can be read independently or as a companion to my article Tiananmen: growing pains of a rising nation, which is extensively referenced. To create this narrative account of those tumultuous seven weeks, I drew on a wide range of sources. To keep it brief, I’ve limited the use of footnotes, but readers are welcome to comment below or contact me by email for additional references.

For an overview of the political situation in the lead up to the Tiananmen movement, and the social forces involved, see Tiananmen: growing pains of a rising nation.

Glossary, acronyms

BSAF: Beijing Students Autonomous Federation

BWAF: Beijing Workers Autonomous Federation

CPC: Chinese Communist Party

CUPSL: Chinese University of Political Science and Law

JLGACC: Joint Liaison Group for All Coordinating Committees

NPC: National People’s Congress

PAP: People’s Armed Police

PLA: People’s Liberation Army

PRC: People’s Republic of China

SESRI: Social and Economic Sciences Research Institute

Simmering Tensions Unleashed

Hu Yaobang dies

April 15, Saturday

Following the sudden death of former General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Hu Yaobang, rumors spread portraying him as a victim of ‘hardline’ leaders like Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping when he was ousted in 1987.

Students quickly mobilise, bringing forward actions originally planned for May Fourth commemorations of 1919 anti-imperialist student protests. They post pro-Hu messages on campus walls, and wreaths with critical political messages are made by students and intellectuals, notably from China University of Political Science and Law (CUPSL) and Social and Economic Sciences Research Institute (SESRI).

For dissident intellectuals, mourning Hu becomes an opportunity for symbolic rejection of the government’s campaigns against “bourgeois liberalisation” (unchecked capitalism) and “spiritual pollution” (rejection of socialist values).

By dusk, workers begin gathering in Tiananmen Square, with numbers growing to over 100 by midnight. They continue meeting daily after work to discuss politics and express frustration at the government and the impacts of economic reforms.

Mourning Turns to Protest

April 16, Sunday

Students across Beijing establish memorials on 26 university campuses in honor of Hu. This evening, 300 students from Peking University march into Tiananmen Square and lay eight wreaths at the Monument to the People’s Heroes, initiating a public display of remembrance.

Leading a contingent, Chen Xiaoping, a dissident from SESRI and CUPSL, pedals a large wreath to the square. Over the next 24 hours, officials analyse more than 700 posters, couplets, and eulogies posted on campuses. While many express sincere mourning, others protest the perceived injustices Hu faced, and some harshly criticise the current political system.

First Major March and Rising Momentum

April 17, Monday

On April 17, the student movement gains momentum as 3,000 students lead the first large-scale march to Tiananmen Square to lay wreaths. 10,000 onlookers gather to watch. City officials, along with police, facilitate traffic, allowing the demonstration to proceed peacefully.

Party officials are instructed to mingle with the students to understand their sentiments and conduct “ideological work”. Instead of calming tensions, their presence creates confusion about the CPC’s stance and unintentionally boosts the students’ confidence in their cause.

Petition, Sit-In, and Escalation

April 18, Tuesday

Students draft the Seven-Point Petition, a list of demands painted onto a large banner: a reassessment of Hu Yaobang, reversal of anti-bourgeois campaigns, press freedom, transparency of officials' wealth, repeal of protest restrictions, better funding for education and academic wages, and honest media coverage of the movement.

These politically charged demands reflect the influence of organised liberal intellectuals within the student leadership. Throughout the day, more student groups from various universities arrive in Tiananmen Square, signaling growing coordination and solidarity.

Later in the day, a sit-in forms in front of the Great Hall of the People, on the West side of the Square. Student leader and PhD candidate from Peking University Li Jinjin helps present the petition to officials who agree to receive it publicly. Li urges students to disperse, believing their goal has been achieved, but the crowd continues to swell with new arrivals.

That night, around 2,000 students and supporters move to Xinhuamen, the entrance to Zhongnanhai—the Party’s central compound— just west of the Square, demanding a dialogue with Premier Li Peng. Tensions rise as protesters clash in a push-and-shove match with guards. Despite attempts to enter the compound, the crowd is eventually persuaded to disperse by early morning, with help from a growing police presence.

The night ends without injuries, but it marks a significant turning point—the peaceful tone has begun to strain under growing pressure and rising expectations.

Meanwhile, workers form a preparatory committee for the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation (BWAF).

More Clashes at the Gate

April 19, Wednesday

By nightfall, around 20,000 people gather in Tiananmen Square, including 3,000 to 4,000 students. A few thousand students march again to Xinhuamen, demanding to deliver a letter directly to the top leadership.

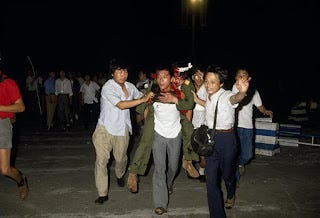

Tensions escalate as students repeatedly try to breach the police line. Military police respond with truncheons, injuring several students. An additional 6,000 to 7,000 onlookers gather at the gate, further fueling the unrest. Police eventually separate the students from the crowd around 1 a.m., with fewer than 300 students remaining. The Beijing municipality sends buses to return students to campuses; over 100 refuse to board, leading to scuffles and a tense standoff.

Despite the unrest, Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang orders police to remove bayonets and avoid violence, emphasising the need to secure the gate without bloodshed. Still, the siege deeply alarms Party leaders—it is the most serious violence directed at state authority in Beijing since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the revolution of 1949.

Radical slogans appear on campus posters, including calls to “attack” and “torch Zhongnanhai,” reflecting rising anger and volatility in the movement.

Growing Tensions and Organisation

April 20, Thursday

Beijing’s campuses buzz with unrest after a sleepless night of protests at Xinhuamen. The mood was exacerbated by news that a student, who had been in the wrong place at the wrong time, was badly beaten by People's Armed Police near Tiananmen Square. Rumours of police brutality spread, stirring anger among students. Calls for a student strike on April 21 gain momentum, with Peking University announcing a class boycott starting at 8 a.m. Students at the CUPSL burn newspapers and smash bottles in anger. At Beijing Normal University, Wu’er Kaixi, standing in the rain, rallies hundreds for a march to Tiananmen Square, but a storm scatters most before they arrive.

Meanwhile, thousands from Peking University also march to Tiananmen through heavy rain. Though larger in size, their protest ultimately dissolves. Throughout the day, groups from multiple universities continue to arrive at the Square to lay wreaths at the Monument to the People's Heroes.

At Peking University, student leader Wang Dan’s Democracy Salon meets to form a planning committee for unified student leadership. Delegates are sent to connect with other campuses, and by early morning, over 2,000 students from Qinghua University arrive to coordinate.

Also outraged by police brutality, the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation forms, marking formal labour involvement.

Protest Deepens, Organisation Grows

April 21, Friday

The BWAF begins officially registering members who can prove their worker status with a work unit ID. They demand action on corruption, wage increases, and transparency of elite wealth.

The government pushes back, criticising the protests and accusing demonstrators of disturbing social order. State media, including People’s Daily, emphasise stability and downplay the unrest. But students find the editorials dismissive and grow more defiant.

While Tiananmen Square is quieter during the day, with delegations from only eight universities and one research institute bringing wreaths, the situation is unpredictable. Several thousand onlookers suddenly rush towards the Great Hall of the People, surrounding three police officers. But it turns out they were either blindly rushing after foreign journalists or following students leaving the Square. The arrival of 50 Tianjin students in the afternoon, parading with their school flags and banners, sparks excitement, drawing 10,000 onlookers, later swelling the crowd to over 40,000.

Ren Wanding, a veteran activist from the 1979 – 1981 Democracy Wall era, gives a speech and narrowly avoids arrest. As night falls, nearly 10,000 students from ten universities arrive to claim space for Hu Yaobang’s memorial the next day, welcomed with hot water and cups from Beijing residents.

Banners now explicitly condemn police violence—the bashing of the student on the 19th backfired. Meanwhile, exaggerated news of student mistreatment spreads to the provinces through U.S. propaganda station Voice of America, sparking unrest in other cities and drawing in unemployed youth who try to incite students to break into government buildings.

At Peking University, the Beijing Students Autonomous Federation (BSAF) is officially founded. Dissident think tank SESRI provides leadership via intellectual Liu Gang’s key role, and material support via a donation.

Memorial and Unrest

April 22, Saturday

Despite government orders to close Tiananmen Square, a massive student rally takes place outside Hu Yaobang’s official memorial ceremony. Nearly 150,000 people gather peacefully around the Great Hall of the People to pay tribute. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) allows the assembly, though plainclothes police are visibly monitoring the crowd.

Party Secretary Zhao Ziyang delivers a respectful eulogy, signaling sympathy for student concerns. Protesters had unsuccessfully requested Hu’s coffin be driven around the square, that Premier Li Peng meet them in person, and that the day’s events be reported in the press.

Three students kneel in front of the Great Hall, presenting the Seven-Point Petition. Their dramatic, imperial-style plea for reform and dialogue goes unanswered for half an hour, and many fellow students feel the gesture is humiliating.

Meanwhile, reports of the Beijing protests and class boycotts spread to the provinces via Voice of America, but direct impact varies. Violence erupts in provincial cities Xi’an and Changsha with riots breaking out involving students, workers, farmers, and unemployed citizens. Over 400 people are arrested across both cities. In Xi’an, police and security forces—caught unprepared, and despite instructions not to react with violence—respond with severe beatings. Military police and public security officials are also injured in the fighting. Authorities suspect criminal elements exploited the unrest, and take defensive measures, including organising work-unit worker militias to keep order.

Momentum Builds, Leadership Splits

April 23, Sunday

Zhao Ziyang departs for a pre-planned visit to North Korea, missing critical meetings on April 24 and 25. Before leaving, he reiterates his three-point approach: firmly prevent the students from demonstrating and get them to return to classes immediately, use legal procedures to severely punish all who engage in beating, smashing and robbing (three terms correlated with Red Guard violence during the Cultural Revolution), and, most importantly, to use persuasion, through multi level dialogues. He had earlier already instructed the press to present the students in a favourable light in order to reduce tension. It is not difficult to see he left contradictory messages behind him at a crucial point in time.

On university campuses across Beijing, student activism intensifies. Class boycotts expand, with some students taking over campus broadcast systems, locking classrooms, and distributing leaflets. Anger runs high, and Party leaders respond by sending officials to “listen” and persuade students to return to class—but with little effect.

The movement consolidates. Representatives from 21 universities gather at the CUPSL to form a provisional student committee, rejecting the legitimacy of official student bodies. Their new demands include a reassessment of Hu Yaobang, freedom of the press, increased education funding, reevaluation of past student protests, and transparency around police violence.

In Shanghai, the World Economic Herald defies Party orders and publishes a call to reassess Hu Yaobang’s legacy. Edited by a Party member, the paper's defiance signals a deeper internal rift. For the first time, elements within the Party visibly align with the student movement, suggesting an emerging split between rightist and leftist factions.

Escalating Concern and Hardening Lines

April 24, Monday

Beijing mayor Chen Xitong realises that sending officials onto campuses to persuade students has failed. The government acknowledges the need for a stronger response as campus activism continues to grow.

Party leaders increasingly blame “reactionary elements” and dissident intellectuals for the unrest, accusing figures from the old Democracy Wall movement of stirring up turmoil. Beijing Party Secretary Li Ximing denounces “black hands” and provocateurs, alleging that students are being guided by dissident Fang Lizhi’s wife, Li Shuxian.

Li Peng, alarmed by reports of the provincial rioting and the disruption of transport links near Wuhan, declares the situation "turmoil," reminiscent of Cultural Revolution days, that must be halted quickly through legal measures.

At Peking University, the scale of the movement becomes undeniable. Around 80% of the student body attends a mass meeting, and students form a 200-member monitoring team with armbands to maintain order.

Mistrust, Defiance and Censorship

April 25, Tuesday

A delegation from the State Council, the National Education Commission, and the Beijing city government arrives at Qinghua University for a dialogue with students. Though the meeting is officially student-initiated, panic spreads on campus. Fearing the label of traitors to the movement, most students boycott the event.

Meanwhile, the BSAF holds its first general meeting. During the session, students listen to a preview of a new People’s Daily editorial scheduled for release the next day. They begin debating whether to stage a mass demonstration on April 27 in response.

"Turmoil" Declared — The Party Draws a Line

April 26, Wednesday

The People’s Daily publishes a sharply worded editorial titled “Take a Clearcut Stand Against Turmoil”. It acknowledges student concerns about corruption and calls for reform under Party leadership. But it draws a harsh distinction between “ordinary students” and unnamed leaders accused of orchestrating a “planned conspiracy” to destabilise China and overthrow socialism. The term dongluan (“turmoil”) evokes the chaos of the Cultural Revolution and frames the protests as a national threat.

The editorial claims that continued unrest endangers China’s progress—economic reforms, legal development, and the socialist system itself. It warns that the nation risks returning to chaos unless protests stop. In its final lines, it questions the movement’s patriotism, calling on all citizens and “patriotic democratic personages” to resist the unrest.

The message offends students, whose leaders condemn the portrayal of their movement as unpatriotic and reactionary. In response, the BSAF holds a press conference to announce a protest for April 27. Meanwhile, campus officials pressure student organisers to call it off. At Peking University, the vote narrowly goes against participating, but dissent remains.

On this day, authorities declare the BWAF illegal.

In Shanghai, the World Economic Herald pushes the boundaries further by publishing the proceedings of a recent symposium organised by intellectuals—defying orders from the city mayor. In response, editor Qin Benli is sacked and the paper is officially shut down, signaling that, despite press openness, certain lines cannot be crossed. Outrage at the move draws more students into the movement in Shanghai and elsewhere.

A Sea of Protesters in Beijing

April 27, Thursday

Around 50,000 students march through Beijing in defiance of the government’s warning, the largest so far. The march is highly disciplined and orderly; students avoid confrontation, leave the square swiftly. The sheer size of the crowd prevents any police action.

The BWAF joins the protest, signaling worker involvement. Across China, major cities see large demonstrations for the first time, sparked by outrage over the April 26 editorial.

The Party responds by softening its public tone. A new government statement suggests channels will be opened for students to voice grievances, but promises harsh measures for rioters and looters.

Meanwhile, the protests adapt tactically. Students outwardly show support for socialism and the Communist Party, waving red flags and moderating slogans. Behind the scenes, however, many still harbour desires for deeper political reform. Foreign media also pick up on the change, reporting that students appear to temper their demands.

State media announces the government’s willingness to hold talks with students, signaling a new phase in the standoff.

A Pause and New Moves

April 28, Friday

The day after the massive protest, Beijing is quiet. Student activism picks up again by the afternoon, especially on university campuses.

At Peking University, graduate students formally vote to disband their official Graduate Student Union, following legal procedures. It is one of the few orderly actions taken during the movement.

Meanwhile, prominent student leaders Wang Dan and Wu’er Kaixi hold an unsanctioned press conference at the Shangri-La Hotel. Speaking mainly to foreign reporters, they claim their lives are in danger and announce plans to go underground (they don’t!).

The Government Reaches Out

April 29, Saturday

The government adopts a more conciliatory tone and holds its first official talks with student representatives. The event is publicised, but the student participants are mostly from official student bodies, not the new autonomous groups.

Prominent leaders like Wu’er Kaixi refuse to attend, rejecting the legitimacy of a dialogue that excludes the BSAF.

The meeting, hosted by State Council spokesperson Yuan Mu, feels more like a press conference than a genuine exchange. Yuan controls the conversation, avoids follow-up questions, and sticks to official lines.

Despite the government offering some small concessions: a stop to the import of luxury cars for officials, no more elite Party meetings at the seaside resort, Beidaihe, and a softer editorial tone from People’s Daily, students are sceptical of the process, and push to choose which government officials should participate in future talks—a demand the government rejects as unworkable.

Students Push for Recognition

April 30, Sunday

The BSAF establishes a formal Dialogue Delegation in an effort to gain official recognition and initiate direct talks with the government.

This move comes in response to the government’s ongoing refusal to engage with unofficial student groups, while continuing to meet with representatives from official student bodies.

Rising Tensions and Demands for Dialogue

May 1 – 3, Monday – Wednesday

On May 1, the BSAF and the Preparatory Committee from Peking University hold a joint press conference, attracting over forty international reporters. The standoff between students and authorities grows more intense.

At Peking University, internal struggles deepen between student leaders. Wang Dan narrowly retains a position on the standing committee. Shen Tong loses and shifts to the Dialogue Delegation.

On May 2, the BSAF delivers a list of twelve preconditions for dialogue with the government. These include demands about delegate composition, official ranks, equality in speaking rights, and media coverage. Students warn they will launch a mass demonstration on May 4, the seventieth anniversary of the historical May Fourth Movement, if there is no adequate response. Emboldened by the government's softer tone but frustrated by slow progress, they give the regime 48 hours to comply.

By May 3, government spokesperson Yuan Mu responds with a mix of threats and conciliatory gestures. He assures students that no force will be used against the planned May 4 demonstration, while also hinting at future punishments. The situation remains on edge.

Peak Before a Lull, Contradictory Speech from Party Secretary

May 4, Thursday

On this auspicious day, the Chinese government sponsors official commemorations, trying to align itself with the spirit of reform. Despite this, the student demonstration is smaller than on April 27. Estimates vary, but numbers drop to around 20,000 - 30,000 students, though more schools are represented. The Beijing mayor credits government propaganda and outreach for the reduced turnout. A lighter, less fearful atmosphere among protestors is noted. There are many tens of thousands of onlookers.

That morning, 10,000 youths publicly join the official organisation, Communist Youth League, pledging loyalty to official reforms and communism.

Zhou Yongjun announces an end to the student class strike, urging students to return to class—a move that stirs controversy and later leads to his expulsion from BSAF. Student leader Wu’er Kaixi emphasizes that the movement stands for freedom, human rights, and rule of law.

At the Asian Development Bank meeting in Beijing, Zhao Ziyang delivers a major speech, signaling a conciliatory approach to the protests. He downplays the threat of turmoil and suggests the students' demands are not anti-Party but, rather, calls for correcting mistakes. This directly contradicts the harsher line from the April 26 editorial and stuns many Party cadres, while emboldening reformists and liberal activists. By contrast, many provincial Party leaders complain Zhao was not conciliatory enough.

Although Zhao's speech calms protests in Beijing for a time—with between 50% and 80% of classes resuming at universities—unrest grows in the provinces. The Party leadership is becoming more deeply divided, with Zhao’s public stance seen as a direct challenge to leftists like Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping. Zhao ally Bao Tong’s efforts to widely broadcast the speech further heighten the internal split, creating confusion among officials and strengthening the student movement’s morale.

International observers also note the shift, interpreting Zhao’s remarks as evidence of an emerging power struggle at the top of the Chinese leadership.

A Quiet Week prompts Hunger Strike Plans

May 5 – 12, Friday – Friday

The student movement in Beijing loses momentum. Most students return to class and the demonstrations are smaller and more directionless. Relief spreads among students after Zhao Ziyang’s conciliatory May 4 speech, yet frustration remains as the government still refuses to meet with the Dialogue Delegation.

On May 5, the internal split within the leadership becomes more pronounced. Zhao’s Asian Development Bank speech has increased nervousness in the Party leadership, and there is internal confusion about whether it had official approval. Meanwhile, the Preparatory Committee at Peking University debates whether to continue the class strike, revealing continued divisions within the student leadership.

By May 6, only Peking University and Beijing Normal University maintain the class boycott. On May 9, emboldened by a relaxation of media controls, around 1,000 journalists petition for greater press freedom, organised by SESRI intellectuals. Students show their support on May 10 by staging a mass bicycle demonstration through Beijing.

At a Politburo Standing Committee meeting on May 10, Zhao Ziyang proposes a five-point plan to resolve the protests through transparency and reform, but finds little support beyond NPC Chairman Wan Li. Tensions rise further as reports of worker unrest emerge from the Fangshan mining area. Party elder Yao Yilin raises the possibility of using force.

On May 11, student leaders debate launching a hunger strike to regain momentum, hoping to leverage Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s upcoming visit to force the authorities to the negotiating table beforehand. At the same time, Zhao ally Hu Qili, secretary of the Central Secretariat of ideology and propaganda, continues to encourage positive press coverage of the movement. Dialogue between the government and students remains stalled, despite official outreach efforts to factories and institutions.

Finally, on May 12, Wang Dan and firebrand graduate student leader Chai Ling initiate the hunger strike. Initially met with little enthusiasm, Chai Ling’s impassioned speech in the evening galvanises many more students to join. Under mounting pressure, the government finally contacts the Dialogue Delegation after midnight, as a new phase of the movement begins.

Hunger Strike Ignites Mass Sympathy

May 13, Saturday

The hunger strike begins in Tiananmen Square with modest support—around 100 students participate initially, unprepared for a prolonged standoff and expecting the government to respond quickly. Over the next two days, numbers grow to 6,000 before settling around 3,000, even as overall student presence in the square starts to wane.

The hunger strike captures the imagination of ordinary Beijingers, deeply moved by the symbolism of voluntarily foregoing food in a country long haunted by famine. The students’ slogans against corruption and for government accountability resonate widely, sparking sympathy and mass support.

By the evening, onlookers had swelled to 100,000. Beijing intellectuals march to the square, in support of striking students “Intellectuals must no longer remain silent!”, “Let us write history!” On the other hand, about 300 professors and young teachers at Peking university wrote a letter to Party central and other centre leadership bodies with an evaluation from their observations and some precautionary advice.

Worker activists leaflet among Beijing’s work units. Daily demonstrations involving 100,000 – 300,000 people spread across the city for the next three days.

The hunger strike is not uniformly strict, with some students not fully observing it, a nuance often overlooked in Western media coverage. Meanwhile, Yan Mingfu from the Party’s United Front Office visits the Square in an attempt to negotiate an end to the hunger strike, offering himself as a personal guarantee for dialogue, but talks collapse amid the chaos of Wu’er Kaixi’s dramatic fainting.

Senior Party leaders meet with more urgency and frequency. Party elder Chen Yun, one of the 1949 founders of the PRC, asks “If we don’t call this turmoil, how can we face the memory of the tens of thousands of martyrs who shed their blood for China’s revolution?”1

Student Intransigence Increases

May 14, Sunday

Throughout the third week of May, government leaders meet students three times in unsuccessful attempts to persuade them to leave Tiananmen Square before the Sino-Soviet summit with Gorbachev. One meeting collapses when hunger strikers march in, angry after a miscommunication over a promised live broadcast.

Meanwhile, twelve intellectuals visit the square to convince students to end their hunger strike. Though they are initially welcomed when they praise the students, the mood quickly sours when withdrawal is suggested, and the tone is perceived as patronising.

Hunger Strike Disrupts Gorbachev’s Visit

May 15, Monday

Around 1,000 students are on hunger strike in Tiananmen Square, according to student leader Li Lu’s survey, though some sources claim up to 1,500. Nearly 100 had now fainted, and one was barely dissuaded from attempting to immolate himself.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s arrival forces the government to abandon tradition by welcoming him at the airport instead of the Square. The government believes that tolerating some diplomatic embarrassment is preferable to yielding to students it sees as unruly, disorganised, and unwilling to follow proper procedures or establish accountable leadership.

Wu’er Kaixi tries to persuade students to clear the area in front of the Great Hall of the People to allow a ceremony, but this decision badly damages his reputation among fellow protesters.

Internal student conflict grows as Chai Ling and Li Lu are challenged over their unelected leadership, while the protest movement spreads to other cities, with new hunger strikes, encampments, and small-scale worker action, for example, 130 former uranium mine workers come to the capital of Xinjiang to conduct a sit-in to demand action on their long-ignored problems of radiation sickness.

100 intellectuals sign a letter in support of political prisoner Wie Jingsheng, a long-time recalcitrant critic of one-party rule. Yan Jiaqi, a senior think tank intellectual and Zhao advisor, is quoted in a French newspaper declaring the winds of democratisation blowing from Russia would be irresistible in China.

That evening, tensions spike when a large crowd threatens to storm a state banquet for Gorbachev; Chai Ling leads weakened hunger strikers to face them down and defuse the situation. Gorbachev’s visit temporarily delays any government crackdown, prolonging the standoff.

Zhao’s Misstep and Rising Tensions in the Square

May 16, Tuesday

Zhao Ziyang meets with Gorbachev and publicly implies that former Party Secretary and current Central Military Commission Chairman Deng Xiaoping still essentially controls China, rather than the five-person Politburo.2 This unprecedented comment exposes internal power struggles to the world and tips the balance against Zhao within Party leadership, his actions seen as undisciplined and disloyal.

That same afternoon, Yan Jiaqi publicly denounces Deng as an "old and fatuous dictator," marking the first time Deng is directly targeted during the movement. Calls to end "rule by elders" begin to spread.

Meanwhile, Tiananmen Square becomes increasingly chaotic. Students faint in growing numbers, ambulance sirens echo constantly, and marshals form human chains to clear paths for emergency vehicles.

Radicalism among some students rises but accusations of cheating emerge within the hunger strike camp. Disillusioned students from the CUPSL break away to form a stricter, independent hunger strike near Xinhuamen.

Mass Mobilisation

May 17, Wednesday

Early that morning, the Party’s top leaders meet at Deng Xiaoping’s home. Martial law is proposed. Zhao Ziyang is isolated and effectively stripped of influence, although his formal resignation is rejected.3 News of Zhao’s fall leaks to the students within hours through Zhao-aligned staff, heightening tensions in the Square.

An estimated 1.2 million people march in Beijing, massively boosted by Beijing residents and organised work units, including staff from government ministries, army logistics units, and state enterprises. Many participants are mobilised through the Party networks controlled by Zhao Ziyang, who is now fighting for political survival by encouraging mass protest.

The Western media celebrates the workers’ presence as grassroots activism, but insiders note that the scale is only possible with high-level support. Trucks, banners, and supplies flow freely, signaling significant establishment backing.

Slogans supporting Zhao appear. Although an overthrow remains unlikely without army backing, Party leaders—haunted by memories of the Cultural Revolution—fear the worst.

Meanwhile, the hunger strike in Tiananmen Square intensifies. Over 2,000 students are now participating, with many collapsing from exhaustion. Efforts by Chai Ling and Li Lu to find an exit strategy fail, as fresh students continue joining. The movement teeters on the edge of chaos.

Martial Law Plans Advance as Conditions Worsen on the Square; Confrontation in the Great Hall when Li Peng Meets the Students

May 18, Thursday

Senior Party elders, Standing Committee members (excluding Zhao Ziyang), and Central Military Commission leaders meet to finalise plans to impose martial law. Their goal is to consolidate Party and military support to end the protests.

The night before, cold and rainy weather batters the students in Tiananmen Square. Despite their vulnerability, hundreds of city buses arrive to provide shelter. The Beijing municipal government organised this aid to prevent student deaths, which, with emotions in the city on edge, would have been disastrous for the authorities.

As the hunger strike enters its fifth day, the number of protesters swells once again. Meanwhile, the Square becomes increasingly unsanitary, with fears of a cholera outbreak adding to the atmosphere of unease.

In a televised event, four Politburo Standing Committee members—Zhao Ziyang, Li Peng, Qiao Shi, and Hu Qili—visit hospitalised hunger strikers, a divided leadership struggling with the unfolding crisis.

Premier Li Peng also meets hunger-striking students inside the Great Hall of the People. The extraordinary event is televised.4 Student leader Wu’er Kaixi, cutting off Li Peng early on, presents four tough demands, including a public apology for labeling the movement as "turmoil" and the promise of open, direct dialogue. He implies student deaths are imminent and criticises the government’s lateness. His interruptions and confrontational tone shocks observers and frustrates Li Peng.

The officials' primary aim is to persuade the students to end their hunger strike and seek medical help. However, the student representatives give contradictory responses about their ability to influence their fellow protestors. They imply government culpability for any casualties without offering any practical path forward.

Despite Li Peng’s appeals for order to avoid “anarchy,” the meeting ends without resolution. Post-graduate student Xiong Yan declares even without official recognition, history will see the movement as patriotic and democratic.

Zhao’s Last Stand and the Imposition of Martial Law

May 19, Friday

In the early hours, Zhao Ziyang visits Tiananmen Square, apologising to the hunger strikers and pleading with them to end their fast.5 Zhao offers no clear pathway for de-escalation, only vague promises of dialogue. His emotional speech, hinting at looming danger, angers his party colleagues and marks a final break with them.

At the same time, Li Peng and other officials also visit the students, maintaining the party line of concern and urging them to seek medical treatment.

Meanwhile, behind closed doors, Party elders, the remaining Politburo Standing Committee members, and military leaders officially decide to impose martial law. They hope to avoid violence but recognise the urgency of restoring control.

Rumors of martial law spread among the hunger strikers by late afternoon. In response, student leaders end the hunger strike, transitioning to a sit-in, in an unsuccessful attempt to deter martial law. The number of demonstrators has halved, but new arrivals from the provinces continue.

Throughout the day, Zhao’s allies call for a general strike and resistance against the government, further alarming Party leaders. Fearing mass mobilisation, the leadership accelerates plans: martial law will begin at 10 a.m. on May 20, earlier than initially intended. In the early hours of May 20, martial law is publicly announced, and the political situation in Beijing shifts decisively toward confrontation.

Martial Law Begins but Citizens Block the Troops

May 20, Saturday

In the morning, martial law officially begins in Beijing, but the army’s attempt to enter the city through narrow streets lined with highrise buildings is immediately thwarted. Tens of thousands of students, and ordinary citizens such as housewives and retired workers, block the roads with buses, barricades, and their own bodies. Protesters lecture the soldiers, believing the People's Liberation Army is simply misinformed, not hostile.

The student movement, once wary of outsiders, now actively seeks support from workers and residents. Students dispatch teams to factories, and neighborhoods organise reinforcements at weak barricade points. Motorcycle convoys on major roads help coordinate communication between demonstrators.

Soldiers are forced to wait for new orders without advancing or retreating. Despite some troops covertly reaching staging areas, the Party faces a new reality: the peaceful student protest has transformed into a broad civil resistance movement. The leadership is stunned, slowly realising that the army cannot easily reassert control without risking bloodshed.

Beijing Standoff Continues

May 21, Sunday

Between 10,000 and 20,000 students still occupy Tiananmen Square. The mood is festive and confident, with up to 80,000 onlookers gathering nearby. Only about 100 to 200 hunger strikers remain. Students and citizens continue to control central Beijing with a sophisticated network of barricades, using buses to block major roads while maintaining narrow openings to manage traffic.

Meanwhile, National People’s Congress Standing Committee member Hu Jiwei lobbies fellow members for a special meeting (before June 20 as scheduled), and SESRI activists push to unify opposition forces into a broad coalition.

Inside the military, concerns are addressed. Eight generals, upset they were not consulted about martial law, send a letter to Deng Xiaoping and the Central Military Commission requesting that troops not enter Beijing. Senior military leaders visit them personally. Two of China’s last surviving Marshals, Xu Xiangqian and Nie Rongzhen, quietly oppose the crackdown, calling for restraint and warning against bloodshed.

Around this time, U.S. military attaché Larry Wortzel notices preparation for violence.

“Having been moving around the city all day taking stock of events, this attaché was dirty, hot, thirsty, and tired when approaching a roadblock designed to stop the PLA manned by workers [more likely ‘floating population—see Tiananmen: growing pains of a rising nation] on the second ring road in Beijing, near the Bell Tower. Two young men wore PLA ammunition bandoleers over their shoulders filled with one-liter Beijing beer bottles. When offered money for a bottle of beer, a young man replied, “These are filled with gasoline; when the PLA comes after the students, they’ll see what ‘People’s War’ really means. We’ll give it to them.” Two weeks later that is exactly what happened.”6

Power Struggles and New Alliances Amid the Standoff

22 May, Monday

On May 21, graduate student leader Wang Chaohua begins reviving the long-overlooked BSAF. In a meeting with representatives from 50 colleges, she finds strong support for her plan to safely withdraw students from Tiananmen Square and end the standoff.

In the early hours of May 22, Wu’er Kaixi, previously sidelined, storms back into the Square. With Wang’s help, he gains access to the student broadcast station and desperately urges students to relocate to the foreign embassy district, before collapsing. His incoherent plea is ignored and damages Wang Chaohua’s efforts to reassert the Federation’s leadership.

Later that day, former hunger strike leaders return from briefly going into hiding and orchestrate a "Provisional Headquarters," installing Chai Ling as Commander-in-Chief. Zhang Boli convinces Wang Chaohua to withdraw temporarily, promising a future restoration of BSAF that never materialises.

Meanwhile, SESRI’s Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao establish a Joint Liaison Group for All Coordinating Committees (JLGACC) to unify liberal forces and guide the movement. Meeting daily at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the JLGACC advises the students and publishes a widely read broadsheet, News Flash, trying to shape strategy and morale as exhaustion and stalemate deepen.

Zhao Ziyang and Hu Qili are relieved of their duties in the Politburo Standing Committee, effective on this day and made official at the Fourth Plenum of the 13th Central Committee in late June.

The Last Days of May

May 23 – 26, Tuesday – Friday

On May 23, though many troops have withdrawn from the streets, 250,000 soldiers remain stationed just outside Beijing. Troops are visited all week by officials and senior officers, who address their concerns, expose rumours and build morale and unity for a potential confrontation.

After successfully confronting the army once, student protesters begin considering how to wind the movement down, aware that another clash is likely. When three individuals deface Mao Zedong’s portrait in the Square, students detain them and hand them over to authorities, wary of provoking further government action. Hopes for support from NPC Chairman Wan Li fade as he lands in Shanghai instead of Beijing after cutting short a U.S. visit. (Four days later he publicly backs martial law).

On May 24, the newly formed "Headquarters for Defending Tiananmen Square," led most prominently by Chai Ling and Li Lu, takes charge of the movement in the Square.

By May 25, leading students are openly discussing how to end the occupation. Debate stirs among protestors in the Square about whether to remain or withdraw, while newly arrived provincial students boost numbers. BWAF is still agitating and signing up members.

On May 26, Li Lu helps establish a new ‘student parliament,’ which meets overnight to vote on the direction of the movement. Although none of the options support withdrawal, most students in favour of this have already left, skewing the vote towards a more hardline stance. American journalist Philip J. Cunningham interviews Chai Ling on the Square, who expresses deep fear and distrust, speaking of betrayal and even contemplating seeking asylum, which Cunningham considers naive. A new banner on the Monument to the People's Heroes outlines protest demands: convene the National People’s Congress, impeach Premier Li Peng, and end military rule. Recent government silence ends with a TV appearance by Li Peng, ending speculation that Zhao Ziyang might return.

Party members of party committees and government departments are instructed not to attend any protests, or even go as an onlooker or do anything that might encourage the students. Demonstrations in the provinces are beginning to taper off. Some students fear academic repercussions, but strikes persist, driven by determined student leaders.

Fractures and Fallout

May 27, Saturday

Most Beijing students have left Tiananmen Square, but thousands of newcomers from provincial universities arrive, determined to keep the sit-in alive. The atmosphere changes: foreign journalists report increasing wariness among ordinary citizens, as threats of arrest and punishment deter open discussion. Workers face pressure from their employers for involvement, and intellectuals are warned they are on a growing arrest list.

While many believe the sit-in is losing momentum, the government is aware of the emergence of the JLGACC, a potential organising force uniting dissident groups.

Intellectual Liu Gang pushes to unify JLGACC efforts by involving student Li Lu in the Conference, but Li Lu delegates the task to Chai Ling and (husband) Feng Congde. Leading the meeting, the intellectuals painstakingly and cautiously draft a ten-point plan. When news arrives that NPC Chairman Wan Li supports martial law, hope for political change fades further. Amid reports of the worsening financial and sanitary conditions in the Square—filth, disunity, and disorder—the Conference agrees to end the sit-in on May 30.

However, Chai Ling and Feng Congde are appalled when Wu’er Kaixi is put forward as the new student spokesman. They storm out, refusing to back the May 30 withdrawal, casting doubt on the consensus. Later that day, Liu Gang tries to introduce a tactical plan for out-of-town students to shift the movement to their home provinces. But he is obstructed by Li Lu and Chai Ling, who defies the Conference and publicly rejects the May 30 exit date, blaming “elite intellectuals.” This forces the Ten Point Statement to be amended, now extending the sit-in until June 20.

Chai Ling’s Crisis and Developments in Daxing

May 28, Sunday

The government forms investigation units to identify Communist Party members who have participated in the protests, signaling growing determination to suppress dissent.

This same day, Chai Ling gives a stunning and emotional filmed interview to Philip Cunningham. Speaking from a private apartment, she confesses deep disillusionment. She admits to expecting no results from the hunger strike she once led and declares, “You, the Chinese, you are not worth my struggle.” While saying she plans to leave the Square in despair and go underground, she surprisingly returns the next day to resume her leadership.

In the interview, Chai chillingly suggests that only a violent massacre can awaken the Chinese people. “Only when the Square is awash with blood will the people of China open their eyes” she says, though clearly torn and guilt-ridden. She blames rival student factions and connected intellectuals for working to clear the Square and stop a crackdown, fearing their actions will allow the movement to collapse quietly and enable the government to isolate and persecute dissidents.

Meanwhile, a protest action takes place in Daxing County, near Beijing, where students and worker allies—including the BWAF and motorcycle brigades—secure the release of eight detained students. The authorities initially deny the arrests, but the protesters locate them and, after confrontation and stone-throwing at the local public security bureau, retrieve their comrades.

A Tent City Emerges in the Square

May 29, Monday

Large numbers of tents, donated and shipped from Hong Kong, arrive at the protest site. They are sorted into color-coded zones, transforming the northern side of the Square into a tent city.

Though the number of protesters has dropped, the new tents help maintain a sense of activity. The vibrant tarps and canvas give the student command zone at the monument a lively, colourful appearance, even as fewer people remain.

With martial law troops stalled in the Beijing suburbs, Western reporters have a rare chance to see how outdated PLA equipment is. For example, military trucks have to be started with a crank, tanks break down because of mechanical problems, and certain Soviet style armoured vehicles are 30 years old.

Students in some provincial cities even set out on a ‘long march for democracy,’ echoing the Long March of Mao and the Communist Party in 1934 – 1935. But around the country, protest numbers rise and fall in ripples, gradually receding overall. In Hefei province, about two-thirds of students are still boycotting classes. They are concerned that a return without concessions would signify a defeat, and are waiting for the government to give them a face saving exit option.

Mounting Tensions and Shifting Tactics

May 30 – June 1, Tuesday – Thursday

On May 30, a wave of retaliatory arrests for the Daxing actions of 28 May occur. Eleven Flying Brigade members and three leaders from the BWAF are detained. One BWAF member, seized by undercover police, had managed to toss his notebook to onlookers, alerting others. A 3,000-strong protest and sit-in forms at the Ministry of Public Security, led by worker activist Han Dongfang.

Meanwhile, rumors of a military crackdown cause numbers at Tiananmen to continue to decline, now at a few thousand.

Amid this, art students erect a huge statue—“Goddess of Democracy”—bearing a striking resemblance to the Statue of Liberty. It draws large crowds and foreign attention, provoking condemnation from authorities who view it as a symbol of foreign influence, particularly American.

On May 31, protests continue outside the Ministry of Public Security. Foreign press and growing crowds keep pressure on authorities, resulting in the release of the detainees. The BWAF faces increased surveillance, but student leaders finally shift tactics, now accepting BWAF presence in the Square, after relegating their organising centre to the western reviewing platform. A heartfelt public appeal by Deng Yingchao, widow of popular former leader Zhou Enlai, urges students to leave before Children’s Day. Her plea is ignored—signaling that compromise is slipping further out of reach.

By June 1, signs of government escalation appear. Soldiers can be seen marching or jogging on the streets in formation, coming as close as a couple of blocks within Tiananmen. Disputes among student leaders has led to an attempted overnight kidnapping of Chai Ling and Feng Congde. As families visit the Square for International Children’s Day, students clean up in anticipation, trying to present a responsible image.

‘Four Gentlemen’ hunger strike begins

June 2, Friday

A new hunger strike by four older individuals—Liu Xiaobo, Hou Dejian, Gao Xin, and Zhou Dou—adds fresh energy. Organised out of frustration with both official silence and student disarray, the action garners attention. Popstar Hou Dejian’s involvement draws large crowds but also risks depoliticising the protest by shifting the focus toward celebrity.

Meanwhile, foreign observers recognise the protests’ fading momentum. A U.S. intelligence summary notes the students may be hoping that their newly erected “Goddess of Democracy” statue will provoke a government overreaction to revive public support.

In the morning, six Party elders meet with the three remaining members of the Politburo Standing Committee. They decide to clear the square, which they identify as a core organising and symbolic centre of the movement, serving as a command centre of the Beijing movement, and by extension the entire nation. They understand that troops will need to be armed, but most of the elders still hold on to hope the job can be done without casualties.

Party elder Li Xiannian, who went through the 1949 Revolution sums up the sentiment:

“Our People’s Republic was built with the blood of more than 20 million revolutionary martyrs. The achievements of socialist construction came after decades of hard struggle, especially during the last 10 years of reform and opening. We can’t allow turmoil to destroy all this overnight… China will lose all hope if we let turmoil have its way or open the door to capitalism.”7

Elder Wang Zhen didn’t mince words:

“What’s the People’s Liberation Army for, anyway? What are martial law troops for? They’re not supposed to just sit around and eat! They’re supposed to grab counterrevolutionaries! We’ve got to do it or we’ll never forgive ourselves!”8

The Crackdown begins

June 3, Saturday

It’s the final hours before the military crackdown on Tiananmen Square. A fresh crisis is sparked after a traffic accident the previous night, when a police van on loan to a state broadcaster collides with four cyclists, killing three. Though the victims were not students, word spreads rapidly that police have deliberately killed civilians.

In the morning, tens of thousands of furious residents flood the streets, confronting over 5,000 unarmed troops advancing on Tiananmen. Crowd hostility escalates. Troops moving toward Tiananmen are swarmed, beaten, and in some cases kidnapped by angry citizens. Some are stripped nearly naked; others are denied medical help as ambulances have their tires slashed. Entire convoys are ambushed, and a military bus is raided by protesters, who seize crates of ammunition and light machine guns.

The soldiers retreat under pressure, and these clashes become a turning point—triggering both wider unrest and the state’s final decision to act with force.

In another incident, demonstrators intercept a van containing automatic weapons near Xinhuamen gate. They parade the weapons atop the vehicle in front of cameras, further enraging the public. The incident prompts the first tear gas assault by the army to recover the van.

Reports from multiple sources, including U.S. embassy cables and Western journalists on the ground, describe widespread attacks on soldiers and military vehicles in numerous districts across the city.

In the mid-afternoon, the U.S. embassy notes that military police and PLA forces are still restraining from using force. However, the government’s patience is breaking. Martial law headquarters begins broadcasting stern warnings: residents should stay home as troops will now use "any and all means" to enforce order.

Beijing mayor Chen Xitong wrote a report about the events. It shows that news of the rioters’ preparations for violent resistance to the troops’ progress into the centre, and the attacks and sabotage, prompted the government to authorise force if necessary to reach the square, to “quell the rebellion”. At about 5:00 pm,

"the ringleaders… distributed knives, iron bars, chains and sharpened bamboo sticks, inciting the mobs to kill soldiers and members of the security forces. In a broadcast over loudspeakers in Tiananmen Square, the Federation of Autonomous 'Workers' Unions urged the people "to take up arms and overthrow the government." It also broadcast how to make and use Molotov cocktails and how to wreck and burn military vehicles… A group of rioters organized about 1,000 people to push down the wall of a construction site near Xidan [a kilometre west of the Square] and stole tools, reinforcing bars and bricks, ready for street fighting.”9

Behind the scenes, the PLA is given explicit orders. Troops are to cross into Beijing by 9:00 p.m. and clear Tiananmen Square by 6:00 a.m. on June 4—using lethal force if required. Tanks and soldiers move in from all directions.

The American embassy sends eyewitness accounts in secret cables back home:

“8. A Chinese-American journalist reported that from what he had seen at Tiananmen Square, the soldiers did not fight back at first and seemed astounded by the reception they were receiving. He saw students trying unsuccessfully to restrain the crowds. He saw crowds attacking and apparently killing soldiers in a tank they had managed to stop. Emboff [Embassy official] witnessed this same incident, in which two soldiers were roasted alive inside the APC and a third was killed by a mob when he left the vehicle. The journalist tried to stop the crowd from beating one soldier and the crowd turned on him. He was knocked unconscious and awoke in Capitol hospital.”10

As night falls, more violence erupts at key entry points. In the Muxidi district, several kilometres west of the Square, soldiers fire warning shots over the heads of protesters, who remain defiant, pelting troops with bricks and flaming bottles. A few military vehicles speed through dense crowds, the urban fighters erect more barricades in response. Urban fighters disable armoured personnel carriers with metal bars in order to be set alight. Soldiers trapped inside are burned alive after being doused with petrol; others manage to climb out only to be beaten and left wounded in the streets. Photographic evidence confirms at least three soldiers are burned and strung up—seemingly by mobs seeking revenge. Though some student marshals try to restrain the crowds or save wounded soldiers, their efforts are often overwhelmed by waves of fury.

Journalists report scenes of horror and confusion. One BBC crew member describes encountering a mob with Molotov cocktails, their eyes gleaming with intent. He notes the presence of unfamiliar agitators—young men with no student affiliation, armed and ready for violence.

There are many accounts of the violence. I will include more of those in a follow up article. Among them is photo-editor for the Associated Press at the time, Jeff Widener. He describes, from 2:20 in an interview, seeing a dead soldier and the probable fatal bashing of another soldier with “clubs and sticks” by “the mob”. He was also attacked and injured himself.11

By late evening, Beijing is ablaze. Fires and flares light the sky, tracer bullets arc overhead, and the air fills with the smell of burning oil and smoke. From their hotel on Chang’an Boulevard to the east, foreign observers liken the scene to a distant battlefield. Sporadic gunfire continues into the night. While soldiers are now authorised to use deadly force, they still fire into the air or pause between volleys, only aiming at the urban fighters to inch forward.

The final offensive is set. The Square has not yet been cleared, but there is no doubt: the crackdown has begun.

Negotiated exit from the Square

June 4 early hours, Sunday

In the early hours, fighting intensifies as clashes continue between protesters and advancing military forces on the remaining few kilometres west of the Square. Around 2:00 am, north of the square, a group of students and citizens attempt to torch army trucks with petrol. They are quickly arrested. Other armoured personnel carriers (APC) are disabled and set alight. Observers report seeing firelight illuminating the sky from a distance.

The violence escalates. In the northeast corner of the square, near the Goddess of Democracy statue, an APC is disabled with iron bars jammed in its tracks. Three of its crew are beaten to death by demonstrators; only one survives, escorted to safety by student pickets. Pages 40 – 46 of the mayor’s report give a sense of the scale of crowd violence that took place for almost 24 hours. The accounts of the soldiers who were beaten or burned and strung up are verified by photographic evidence, giving credibility to this source.12 This government news cut shows the scale of destruction, with 1280 vehicles destroyed in the riot.

As the situation deteriorates, the square begins to empty. Most civilians and students withdraw, leaving behind a few hundred protestors gathered mainly at the central Monument to the People's Heroes and some workers who remain at the northern edge. Witnesses describe a mood of desperation. By 3:30 am, a small delegation—initiated by two Red Cross doctors and accompanied by two of the ‘four gentlemen’ hunger strikers, Hou Dejian and Zhou Dou—negotiates with military commanders to allow a peaceful student retreat.

At 4:00 am, the square is plunged into darkness as the lights are switched off. By 5:00 am, after news spreads of violence and deaths elsewhere and a negotiated safe exit, students begin to leave through a corridor cleared by troops in the southeastern corner of the square.

A final stand occurs at the monument. Troops push up its steps, shooting the loudspeakers and striking hold-out students with batons to force them to leave. Some are injured in a crush against the fence. By 6:30 am, all remaining protestors have been cleared, except for a few wounded who remain at a first aid station a little longer. The evidence that there were no deaths in the Square is overwhelming. Many people have now documented this—I will pull all the accounts I could find together in a comprehensive future article.

Protestors play with fire

June 4, Sunday

At around 6:00 am, students and citizens retreating from Tiananmen Square reach Liubukou just to the west, where soldiers suddenly open fire and tanks drive into the crowd. Eleven people are killed. I couldn’t find an explanation for this action, presumably emotions boiled over.

By 6:30 am, on Chang’an West Boulevard, again near Liubukou, another crowd confronts the military. Protestors throw bricks at the soldiers who retaliate with bricks and fire tear gas, but the wind and distance limit their effect. Then, from three passing army trucks, gunfire erupts after someone again shouts “fascists,” and eight protesters are wounded.

At the same time, just east of the square, about 100 citizens stand 10–20 metres from military forces, shouting and taunting them for nearly 20 minutes. A colonel then orders the troops to aim their weapons. As the crowd begins to scatter, someone yells “fascists,” prompting the soldiers to open fire. Four people fall, bleeding on the pavement—this is the event likely witnessed by journalists in the nearby Beijing Hotel.

Other Sources of Deaths Caused by Civilian Violence

As military vehicles advanced through Beijing, chaos spread beyond confrontations with soldiers. In Zhushikou, south of Tiananmen Square, crowds halted and destroyed military vehicles. In one case, civilians swarmed a vehicle, and when a man—possibly a government cadre—tried to stop them, the mob severely beat him. His fate remains unknown. Were there similar cases amongst the chaotic frenzy?

Some individuals, having seized rifles, use them recklessly. Eyewitnesses reported that some bystanders were wounded or killed not only by stray bullets or vehicles, but also by other civilians. In one instance, a group commandeered an armored personnel carrier and fired its machine gun indiscriminately.

PLA bullets fired into the air struck people in nearby buildings. Some were hit while standing on balconies or looking out windows. An embassy report notes broken windows consistent with stray gunfire. Journalist John Pomfret confirms that apartment residents were struck by gunfire. When pressed, he cannot say whether it is intentional or simply the result of untrained, panicked troops, but we know troops are on orders not to kill unless necessary.

Death Toll

In the first few days after the crackdown, wild claims abound of thousands or even ten thousand civilian deaths. To this day, the Western media line tends to be “hundreds, if not thousands,” manipulating us through the power of suggestion. In reality, the death toll appears to have been remarkably low, especially in the context of the chaos and scale of the operation. The official death toll is corroborated through multiple sources. In turn, the low death toll corroborates the content of the Tiananmen Papers, a compilation of leaked official records and meeting notes—that the government tried its utmost to limit casualties.

At first, official Chinese government figures acknowledged around 200 civilian deaths, reported at a June 6 meeting between senior leaders and the Politburo Standing Committee. Additionally, they reported over 5,000 wounded PLA soldiers and more than 2,000 wounded civilians. The final official toll was 241 dead, including 218 civilians—36 of whom were students—along with 10 soldiers and 13 armed police officers.

Foreign and U.S. embassy estimates suggest similar numbers. Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times reported approximately 400 deaths overall, based on hospital visits and eyewitness accounts, including possibly a dozen soldiers. John Sheahan of CBS News cited 150 dead and 325 wounded across eight hospitals. The Washington Post described the toll as “scores, possibly hundreds,” while the Los Angeles Times reported “at least 100, and perhaps many more.” The U.S. Embassy in Beijing estimated between 180 and 500 deaths, later refining this to "at most, several hundred." Civil society organisations also provide data: after long periods of investigation, the Tiananmen Mothers group confirmed the identities of 202 victims, while Human Rights in China published a list in 1999 naming 155 confirmed victims.

Contrary to the claims that the Chinese authorities were determined to teach the people a lesson by drowning the movement in blood, the relatively low death toll can be explained.

Protesters attacked military convoys, destroying at least 600 military vehicles, but most of these were set ablaze only after soldiers had been allowed to evacuate, which limited fatalities.

PLA troops exercised restraint. Soldiers were reluctant to fire directly at civilians and frequently discharged their weapons into the air to disperse crowds.

Urban combat conditions also played a role. The military's progress through narrow city streets—rather than across open terrain—hindered progress. This made it easier for people to build blockades, and made military vehicles highly vulnerable to the fighters’ tactics of disabling them with iron bars. Thanks to the minimal use of force by the soldiers, this made progress painstakingly slow but greatly reduced the lethality of their approach to the Square. If tanks really had been used to “mow down protestors,” the civilian death toll would have been in the thousands, and undoubtedly less soldiers and police would have died or been injured.

"Tank Man" — imaginations run wild

In the widely circulated image, taken by a Western photographer, an unidentified man stands alone in front of a line of advancing tanks on Chang’an Avenue in Beijing, just east of the Square, blocking their path. Little did this man know he was providing a largely belligerent West with material for their propaganda arsenal that would be deployed for decades.

In the full footage, however, he can be seen stepping from side to side to block the lead tank, whose driver tries to proceed around him. After succeeding in stopping the tank column, the man briefly climbs onto the lead tank, speaks to the crew, and resumes his position in front of the column. The full video shows reckless behaviour, but no evidence of violence toward him and ends with him being led away by bystanders, unharmed.

Despite decades of speculation, there is no verified evidence that this man—dubbed "Tank Man"—was arrested or executed. Even sources critical of the Chinese government, including Wikipedia, acknowledge that his fate remains unknown and unproven. The article “The Unknown Rebel,” while emotionally charged, offers nothing in terms of confirmed facts.

Multiple credible observers cast doubt on the arrest or execution narrative. Historian Timothy Brook, journalist Jan Wong, and Robin Munro, a Human Rights Watch researcher and eyewitness, all independently state that claims of his execution are unsupported. Munro, after investigating sources used by Western media, concluded that the information was unreliable and speculative.

To this day, the identity and fate of "Tank Man" remain unclear. What is clear, however, is that the narratives about him are built on assumption and ideology rather than confirmed fact.

Aftermath of the Movement

Provincial and Popular Reactions

Protests spread beyond Beijing to many cities, as citizens react to false reports of a massacre in Tiananmen Square. Crowds expressing grief and anger, with some staging memorial-style marches, and violence and chaos in other places, are largely localised. In several cities, protests include workers and unemployed youth.

Judicial Crackdown in Two Phases

Over one thousand people are detained in the months following the protests. While many are released without charge, some are charged and serve sentences. Violent incidents are dealt with first. At least 49 executions have been documented, for crimes of violence against military personnel and destruction of property, such as the burning of three train carriages in Shanghai, with the execution of the three perpetrators.

On the other hand, intellectual leaders and student activists are subject to extended pretrial detentions of around 18 months that may violate Chinese legal standards, but they are treated well in prison. Some of these are eventually released without charge, others receive sentences.

Political Consolidation and Image Management

Initially, unsure of the facts and the fall-out, only a few provincial governments support the crackdown, but Deng Xiaoping’s reappearance on 9 June rallies the Party and military leadership. The government launches a campaign against corruption and elitism, dissolving companies tied to Party elites and reintroduces blue-collar work requirements for university students.

Economic Impact and Recovery

The immediate aftermath of the June 1989 protests sees China facing serious economic setbacks. Western nations impose sanctions and suspend desperately-needed loans, while domestic confidence plummets. Reform efforts stall as conservative factions briefly gain ground. However, Deng Xiaoping reignites reforms with his 1992 “Southern Tour,” bypassing official channels and reaffirms China’s path toward market liberalisation. These measures reverse the stagnation and re-energise development.

Restoring Public Trust in the PLA

The military’s image, somewhat tarnished by its role in the suppression, is gradually rehabilitated through public service initiatives, such as disaster relief during floods. Over time, the relationship between the PLA and civilians is repaired through a mix of policy, public relations, and performance.

Long-Term Characterisation

Given the way the issue is cynically weaponised in the West, commemoration or even discussion of the “1989 political disturbance” has been actively discouraged by the authorities in China ever since, in an entirely sensible approach. The “turmoil” was a political crisis, stemming from the contradictory impacts of reforms on the general populace, and the turning away of a large number of intellectuals from the socialist project. These tensions were reflected in the factional struggle within the Communist Party, followed by a reassertion of control.

Learn more

This article follows Tiananmen: growing pains of a rising nation, written especially for people who are interested in the speculations and colour revolution theories of the event. To provide context, I give a brief economic and political background to 1989 and outline the social classes involved in the movement. I finish with a discussion of twelve “smoking guns” of colour revolution—claims made by pro-China commentators. In this section I argue that the shallow evidence provided does not ultimately serve their cause. Knowing the facts provides us with a more solid footing from which to stand up to imperialist bullying and war.

Forthcoming articles will include:

For people who have only heard the narrative of students “gunned down” or “run over by tanks” by a ruthless government, leaving thousands dead, I will provide a compilation of the credible evidence documenting that there was no massacre in the Square but, rather, pitched street battles between urban fighters and an army acting under orders to reach and clear the Square with as few deaths as possible. Furthermore, I will present additional evidence that the leadership of the Communist Party of China went to great lengths to peacefully resolve the situation.

And finally, a compendium of articles that debunk anti-China propaganda in general.

For collaboration inquiries, email lorrainepratley@hotmail.com

Nathan, A. J. and Link, P. (eds.) 2001. The Tiananmen Papers. New York: PublicAffairs, p. 161.

Zhao Ziyang defended his comments as trying to show that Party leadership was united, but that’s not the way it was taken by either side. Note Deng Xiaoping, given the enormous role he had played in steering China forward, did have an unofficial senior advisory and even decision-making role, and Party elders were contacting him to use his influence to bring the situation under control.

To Zhao’s credit, after trying to resign again on the 18th, he allowed himself to be persuaded out of resigning by President Yang Shangkun, thus preventing another layer of melodrama to an already tense situation. Yang Shangkun played a very important mediating and stabilising role throughout the events.

Transcript: http://www.tsquare.tv/chronology/May18mtg.html; Footage:

More footage can be viewed here: search YouTube for Tiananmen Square Protests 1989: China's Premiere Meets Student Protestors by ABC News.

Footage of Zhao’s speech to hunger strikers:

Wortzel, L. M. 2005. ‘The Tiananmen Massacre Reappraised: Public Protest, Urban Warfare, and the Peoples’ Liberation Army,’ in Chinese National Decisionmaking Under Stress, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, p. 73, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11967.6?seq=1.

Nathan & Link (n 1) pp. 357–358.

Ibid., p. 357.

Chen, X. 1989. ‘Report on checking the turmoil and quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion,’ State Councillor and Mayor of Beijing, 30 June, p. 42, https://museumfatigue.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/chen-xitong_report-on-putting-down-anti-government-riot_1989.pdf.

American Embassy Beijing, 1989. ‘Subject: Sitrep No. 32: The morning of June 4,’ National Security Archives, p. 5, https://web.archive.org/web/20230712065328/https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB16/docs/doc14.pdf.

Note the interviewer’s complete disinterest in the mob violence, turning instead to satiate the Western obsession with Widener’s misused ‘Tank Man’ photo! For the truth about Tank Man, see my article Tiananmen: growing pains of a rising nation.

This compilation contains an image of one of the burned, strung up soldiers: https://worldaffairs.blog/2019/06/02/tiananmen-square-massacre-facts-fiction-and-propaganda/; Injured soldiers: https://www.protestinphotobook.com/post/the-truth-about-the-beijing-turmoil; Injured soldiers and the disabling of military vehicles: http://www.standoffattiananmen.com/2015/06/pictures-of-1989-army-apcs-arrives-at.html.